Automation or Augmentation?

Automation is an increasingly important part of OSINT. Even the simplest of investigations can require large amounts of different data types to be gathered and analysed quickly. Yet it is not accurate to suggest that all OSINT work is going to be automated as time progresses. Good OSINT practitioners will do work that is augmented by automation, rather than replaced by it. A good security analyst, journalist, or detective will still be needed at the sharp end to make sense of the data and evaluate its worth.

Spiderfoot HX is my favourite tool for automated OSINT gathering. It also has some excellent analysis and visualisation features that I’ve written about previously. In this post I showed how Spiderfoot HX could be used to investigate a malicious IP address, and here I wrote about how it could be used to research a domain used for phishing.

In this case study I’m going to show how Spiderfoot’s ability to gather relevant data automatically can be used to augment an OSINT investigation by identifying points of interest to pivot from and explore further.

Target

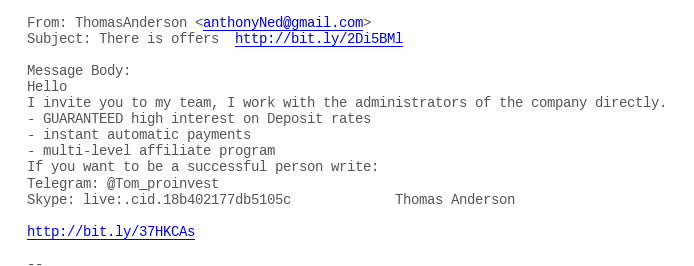

The subject of this investigation came by way of this spam e-mail that I received via the contact portal on this site:

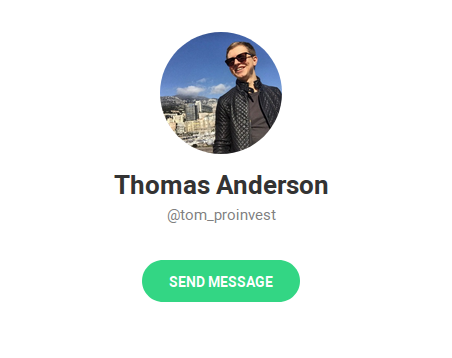

I feel so special! Thomas Anderson (or is it Anthony Ned?) is inviting me to join his affiliate marketing scheme. What can we find out about it? The spam e-mail gives several identifiers that we can feed into Spiderfoot. There’s an e-mail address, a Skype username, and a Telegram account – but I’m really interested in the Bitly links, where do they lead to?

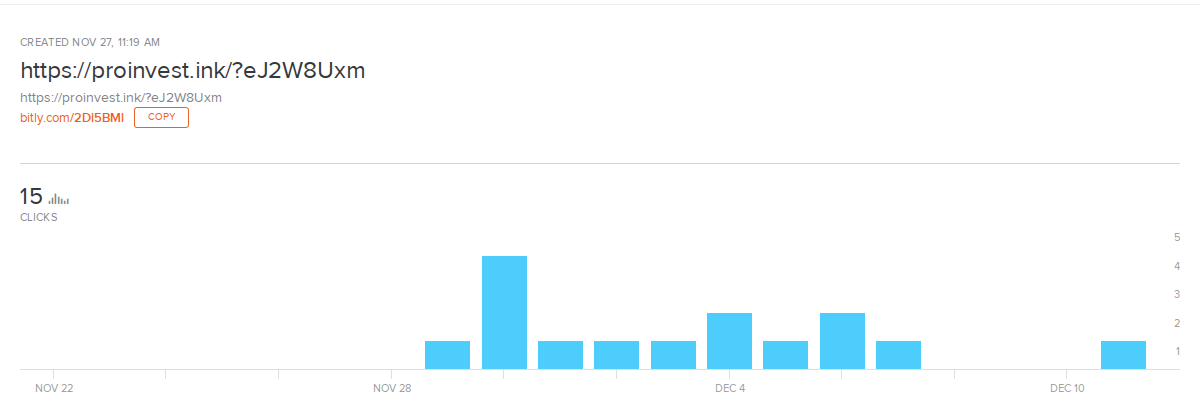

Cyber Security 101 means not clicking on links in unsolicited spam e-mails, but there’s a little trick with Bitly that can help avoid this. Entering the URL in a browser search bar and adding a + sign to the end takes you to Bitly’s analytics page for that URL. So for the first URL in the e-mail Bitly tells us this:

So without needing to click on the link (which could well have been malicious), I already know that the domain behind the spam e-mail is proinvest[.]ink. The second Bitly link also points to the same domain. We can also see that a total of 15 people have clicked on the link, and that it’s only been active since the end of November.

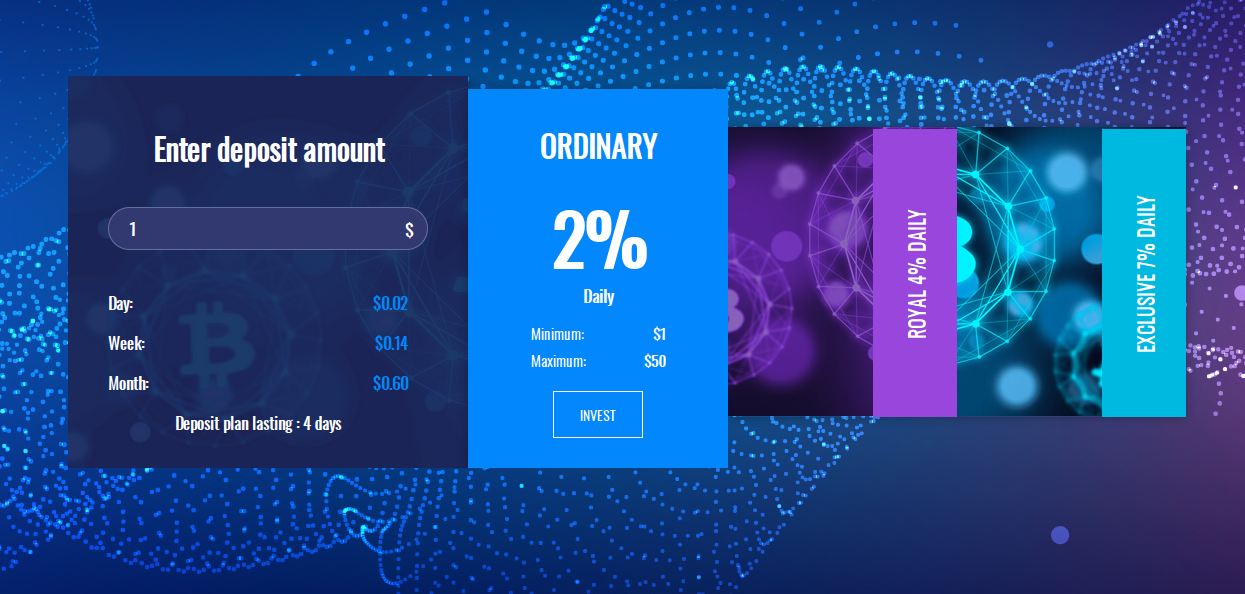

So what do we actually find at proinvest[.]ink…

It’s a crypto currency investment scam!

These kind of scams are increasingly common and have defrauded a lot of innocent people of their savings. The average loss per victim in 2019 was a staggering £14,600 ($19,000). The scams encourage victims to invest their money in Bitcoin or foreign currencies with the promise of quick returns. All seems well at first and the victims are led to believe that they’ve made huge sums of money. They’re then encouraged to invest even more, which most do. As soon as they try to realise their investment however, the scammers make excuses and break off contact before disappearing together with the victim’s money.

Here’s what Proinvest say about themselves:

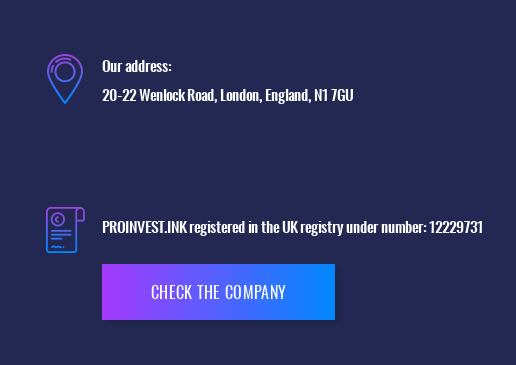

They even provide a real UK address and company details for their operations:

But how legitimate is this investment scheme that I’ve been specially chosen to take part in? We can use Spiderfoot HX to get some insights into how the Proinvest scam operates so we can learn more.

Setting Up Spiderfoot HX

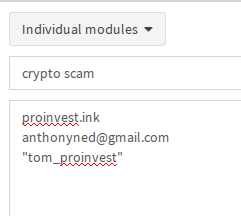

We’re going to use a custom scan to investigate the website. To get started go to Scan and click the + symbol to create a new scan. I’ve called this one “crypto scam”:

I haven’t added much information at this point. I’m just focusing on the domain, the spam e-mail address, and the Telegram handle of “Tom”, who is apparently so keen to make me rich and successful. Spiderfoot HX also allows you to search for phone numbers (be sure to add a + at the start) as well as human names. Human names need to be in inverted commas. I considered adding “Thomas Anderson” to the scan, but a really common name like this is likely to throw up too many false positives, so I’ll leave it out.

Spiderfoot HX has around 170 modules to choose from, but not all of them are relevant to what we want to find out so modules that we don’t need can be disabled to save time and also to make sure that API credits aren’t wasted.

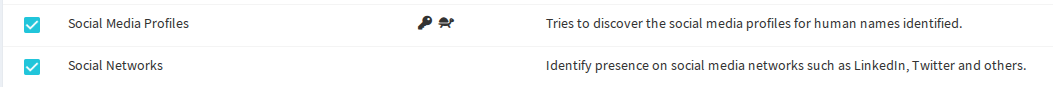

There are some great modules for exploring website content, e-mails, and usernames that we’ll want to enable. These include Archive.org, BuiltWith (API key required), Clearbit (API), EmailRep, File Metadata, Fraudguard, Internal and External URLs, and Web Analytics. Because we’ve got an e-mail address and a username, it’s also important to enable the Accounts, Social Media Profiles, and Social Networks modules to try and learn what we can about the site:

The accounts module checks for username matches against almost 200 different websites, which is even more than Sherlock.

Once you’re ready, click Run Scan Now to start. You can view the results as they come in, or if you’d prefer not to watch and wait Spiderfoot will send you an e-mail notification when the scan is completed.

Scan Results

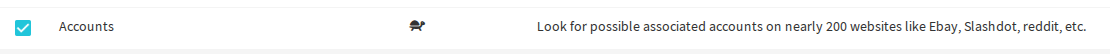

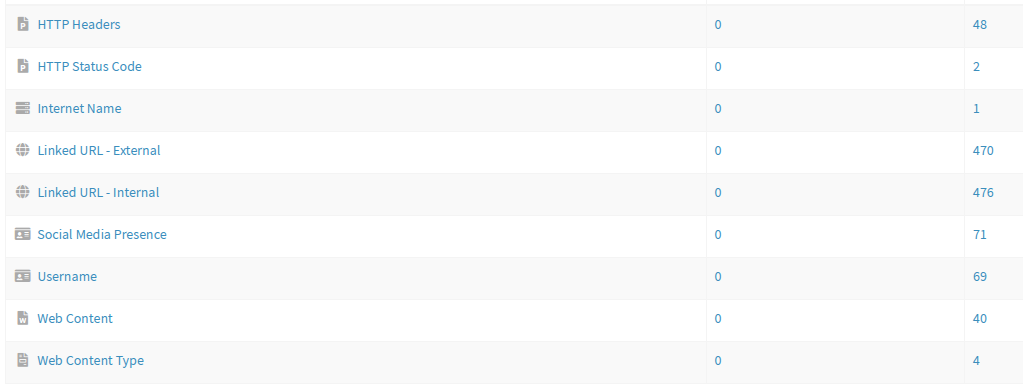

One of the purposes of this post is to show how Spiderfoot’s rapid OSINT automation capabilities can augment an investigation. I enabled a lot of modules for this scan and Spiderfoot returned thousands of data points, almost all of them useful in some way. To get even a small fraction of this information using manual techniques or even a series of locally run scripts would have taken me days, been error prone and likely have missed important data points. The less time I spend gathering information means more time to analyse and investigate the material that was found.

Now the gathering is done, we can use Spiderfoot’s results and visualisation tools to start digging into the crypto scam.

IP and Domain Information

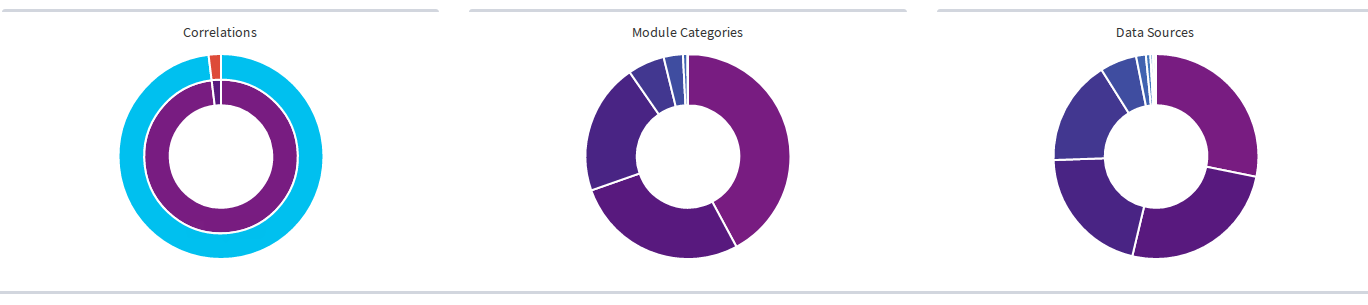

Spiderfoot’s risk identification feature immediately flags that the IP addresses associated to the scam site are malicious:

You can tell a lot about a website from the company it keeps. VirusTotal has previously linked the IP and those around it to malicious activity:

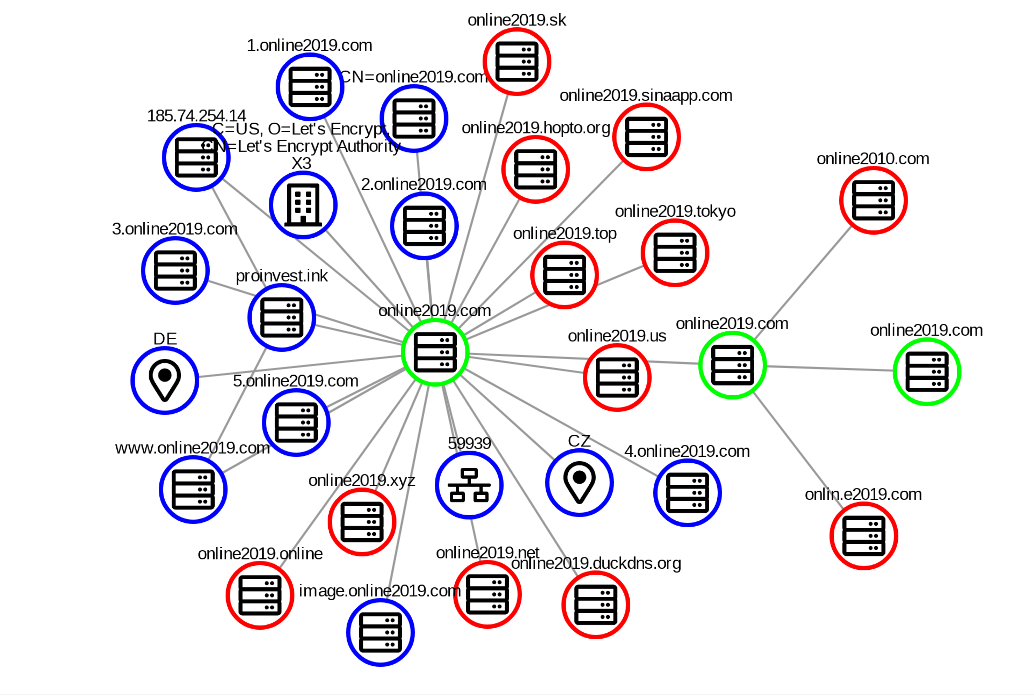

Spiderfoot has also identified another domain on the same IP (Scan Results > Domain Name). It’s the only other domain currently hosted on this IP. We can learn an awful lot about it with the visualisation feature:

The other domain (online2019[.]com) itself isn’t yet classed as malicious, but plenty of its namesake domains are. What does this website actually look like if we (safely) pay it a visit?

Wow! A whole 1 BTC ($7200) just for taking a five minute survey! How lucky am I?

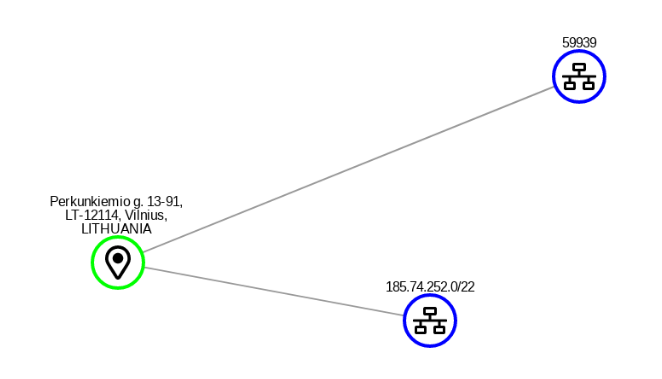

There’s a few other interesting points about the IP address too. Although the IP is allocated to Germany, it’s actually owned by a Lithuanian hosting company. Spiderfoot has managed to pick out the physical address of the hosting company from the data that it gathered (Scan Results > Physical Location).

Here’s the address of the hosting company that one of London’s “top private equity firms” allegedly uses to run its operations:

Hmm. Not sure I’m ready to part with my cash yet.

Verification & Analytics IDs

Even if it wasn’t obvious from the outset that this was a scam website, the IP and domain information Spiderfoot found tends to suggest that perhaps we aren’t dealing with a big London investment firm after all. But what else can we learn? We saw right at the start that the Bitly links used for the spam promotion campaign had only been active for a short time, so what were the team behind this site been up to before then? We can use the captured data to try and find other sites the fraudsters might be involved with.

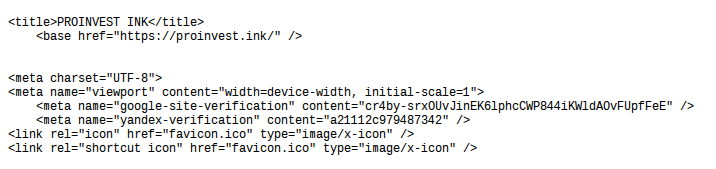

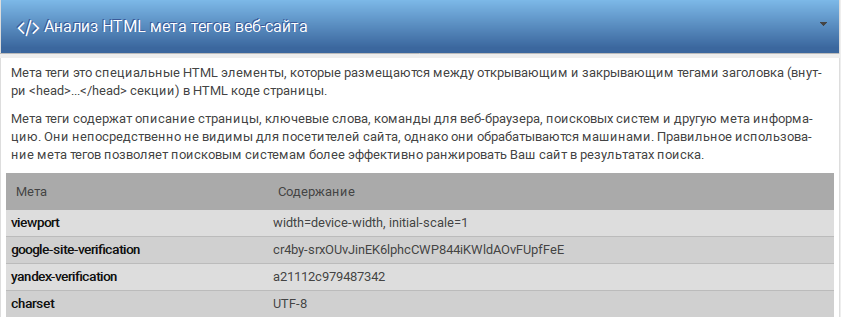

Spiderfoot captures the content of the target website in its raw format, so it’s possible to view the HTML, CSS, and Javascript files without visiting the site directly. In the header of the main website HTML there are analytics tags for both Google and Yandex:

Web admins like convenience just like the rest of us. As a result the same website owner will frequently reuse the same Google Analytics ID across all the sites he or she is responsible for. In this case there are verification codes for both Google and Yandex – this allows the owner to prove that the site is theirs. But where else do they use the same identifiers?

A quick Google search shows that the same pair of Yandex and Google identifiers have been used on two other defunct crypto scam websites, icolimited[.]org and bit-crown[.]com.

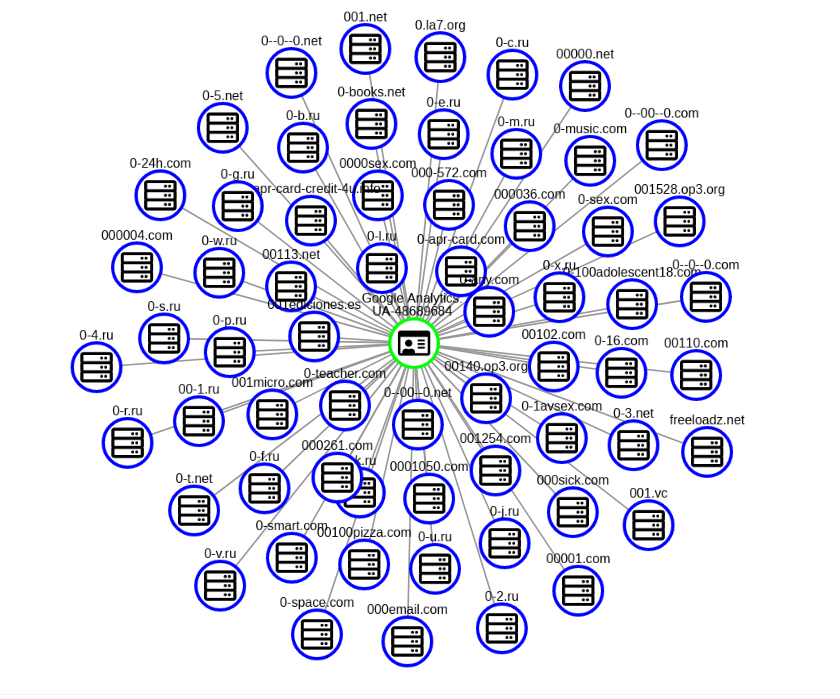

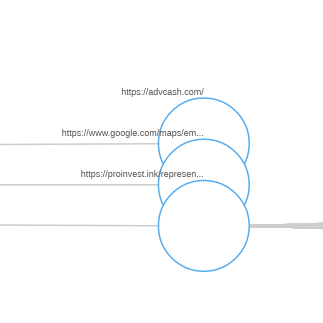

In this case our target website did not actually contain a Google analytics ID, but Spiderfoot automatically pivots through other associated websites, identifies analytics and Adsense IDs, and then uses the SpyOnWeb API to find websites that share the same analytics ID. It’s a fantastic way to make definitive links between multiple sites that are not obviously connected in any other way.

This visualisation of associated Google Analytics IDs is from a domain hosted by the same company as our target site, as identified by Spiderfoot. It shows clearly how one ID can be used to prove a connection between multiple sites:

Documents

What other little nuggets of detail can Spiderfoot dig out from the website that might help us learn a little bit more about who is behind it?

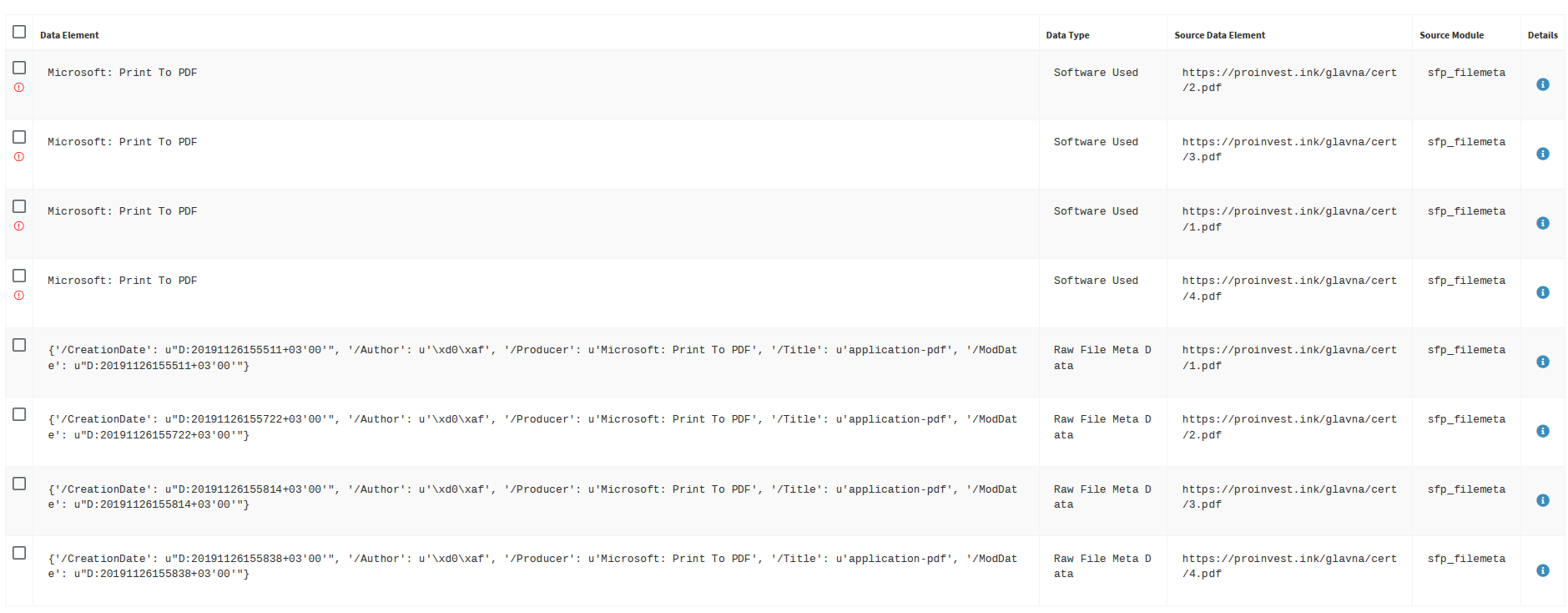

At the start we enabled the File Metadata module to capture information about any files discovered within the website. Here’s what Spiderfoot brought back:

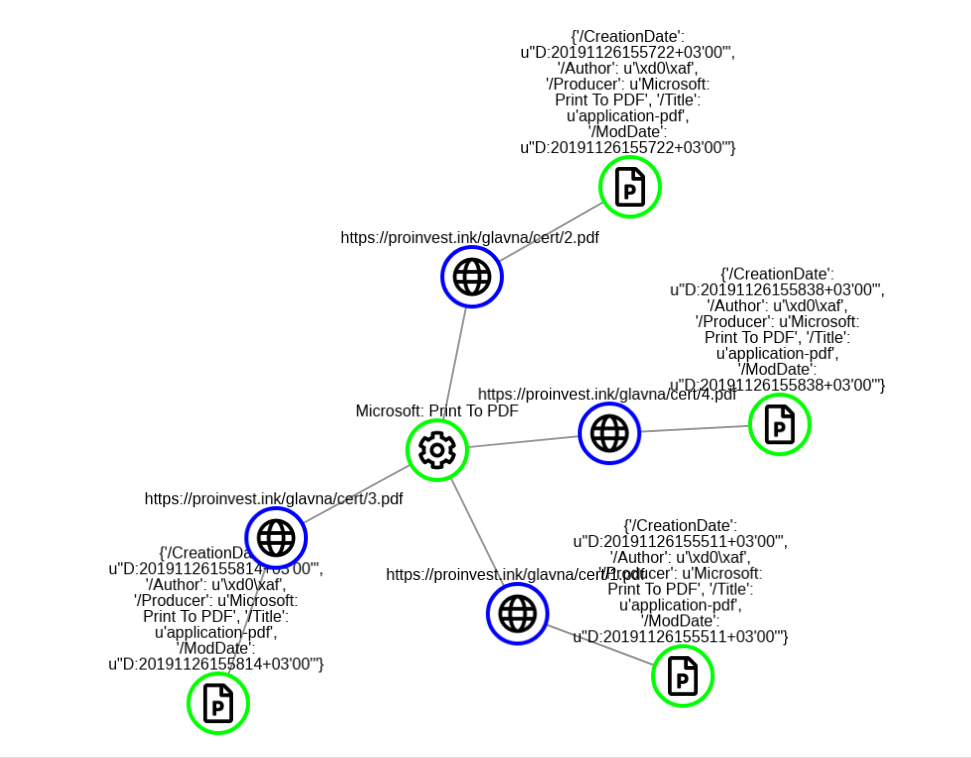

Spiderfoot has identified four PDFs within the website. It’s easier to visualise them rather than trawl through the rows of data:

We can see they were created with a Microsoft product, but there’s some even more interesting metadata associated with each file:

This shows the creation date for the PDFs on the website, which also happens to be the same as the last modified date. The PDF was created on 26th November 2019 at 15:55:11, but look at the time zone: +03’00. Computers use UTC as a reference point, which also happens to be the same time as in the UK. So why does our “London based” investment company’s computer have a timestamp that is 3 hours ahead of London time? Here’s a suggestion as to why:

All of these countries are in the UTC +3 time zone part of the year, but on the date this file was created only Belarus and Russia were in this time zone. This is an indication as to where the creators of the scam website are really located. The timestamp on the file reflects the time of the local machine that the file was actually created on, so it allows us to be confident about where the creator of the site is located.

But what do these PDFs actually refer to? Let’s have a look at one of them:

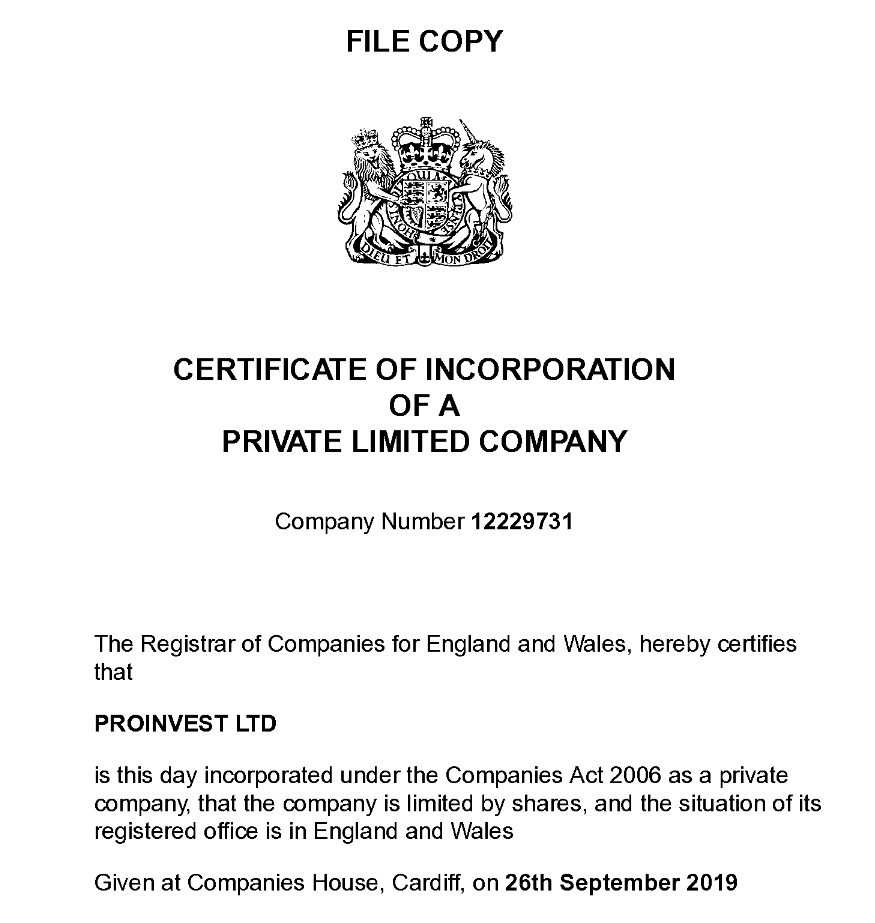

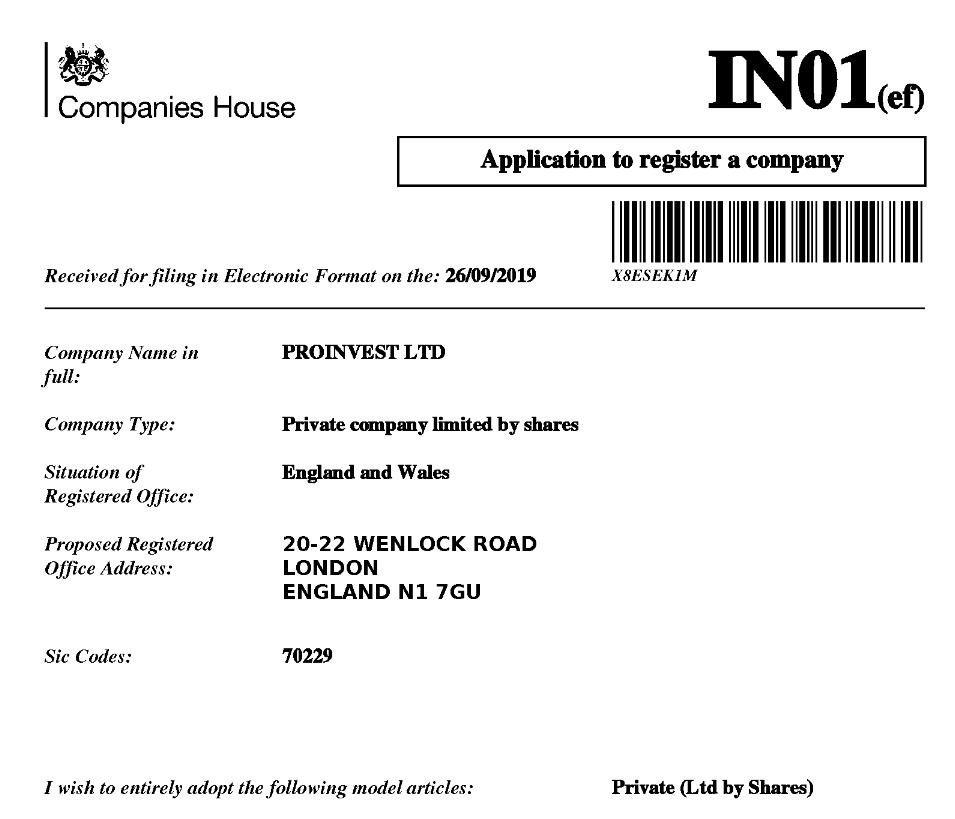

These are documents from Companies House, where every business in the UK is required to register. If we try to verify whether these details are correct or not we find that Proinvest Ltd is a real UK-based company. The director is named as Piotr Antoni Kaszynski. He’s also registered as a director of multiple companies back in his native Poland. It’s tempting to assume that he’s behind the scam – but this information is not quite what it seems.

Even the address in the Companies House listing isn’t actually all that helpful. 20-22 Wenlock Road is a real address but it’s just a virtual office for companies to register at. There’s no physical link between this address and the actual location of the fraudsters. It’s not surprising that these kind of setups are attractive to criminals.

The question is – is the Proinvest Ltd company listed in London the same Proinvest company behind the scam website? The answer to that is no. All financial companies in the UK are required to be licenced by the Financial Conduct Authority. Unsurprisingly Proinvest[.]ink are not. They are a clone company and are using a genuine company’s name and registration details to make their fraud seem more plausible.

The file metadata module also reveals something of the structure of the website itself. The filepath to the PDFs we just looked at is proinvest[.]ink/glavna/cert/xxxx. “Glavna” is Russian for “main” – so there’s another clue as to the true origins of the website.

How Are Victims Recruited? With A Sock Puppet Army.

I was targeted by the scammers using a spam e-mail from “Thomas Anderson”, but how else are the fraudsters recruiting victims? Persuading people to keep on parting with their money takes a lot of time and effort – and a lot of sock puppets. Once again Spiderfoot uses the site content to map and identify the sock puppet network very quickly.

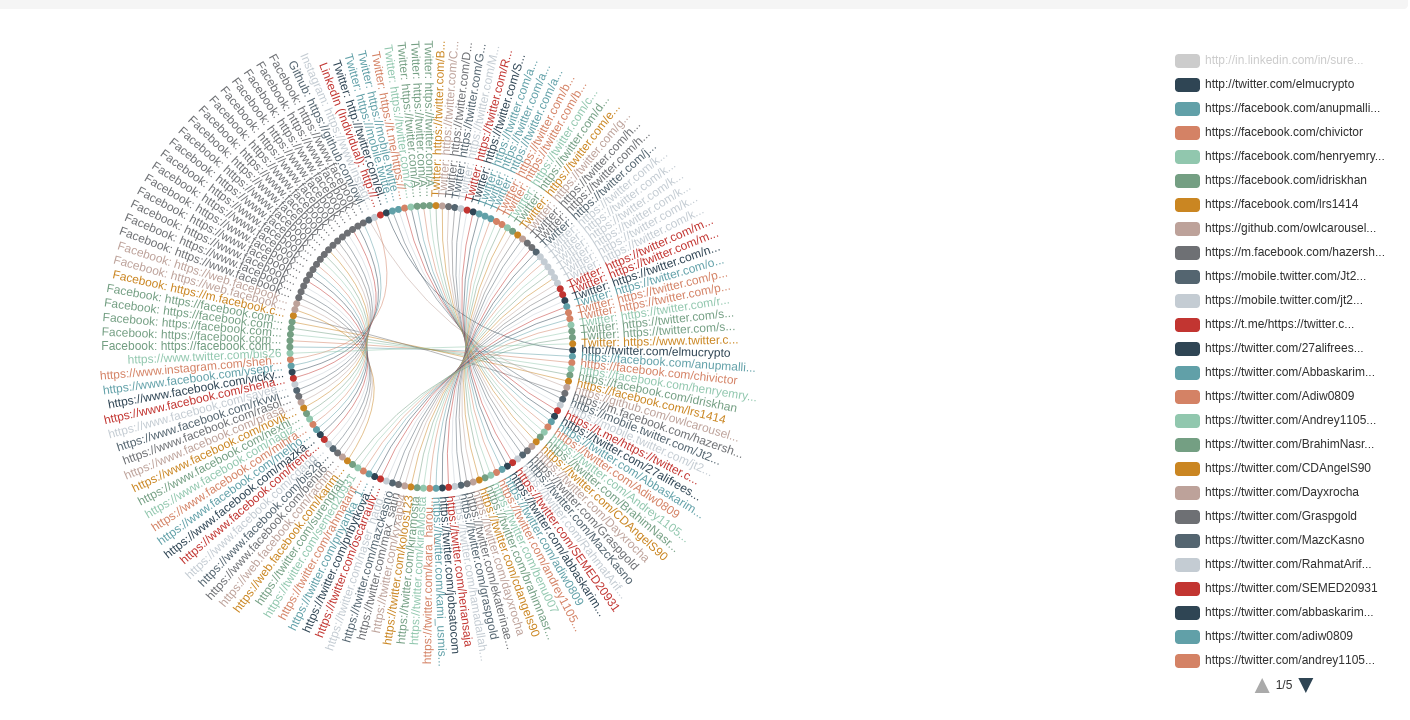

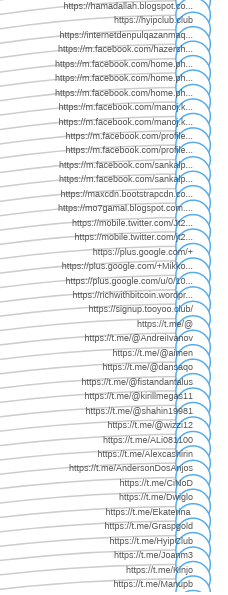

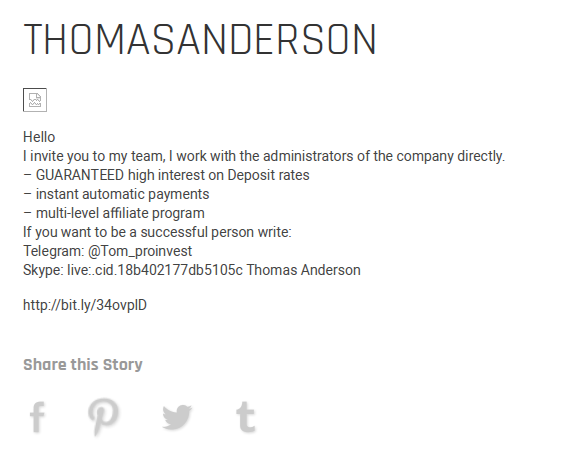

From the results, select Browse By > Data Type > Linked URL – External. This shows all the external web pages that the scam site points to. A sock puppet named “Thomas Anderson” tried to recruit me in the first place – but “Tom” is just one of hundreds of sock puppet accounts created for the purpose of perpetrating the fraud. These happy and successful “representatives” are the means by which the scammers communicate with the victims. Spiderfoot is going to find all of them very quickly indeed – and there’s well over 400.

To see the results, choose Discovery Path (Left > Right):

The discovery path lets us see how every single search result is connected to the original query. This is a large visualisation, so I’ll break it down so that it’s easier to see. Here’s the original query we gave Spiderfoot:

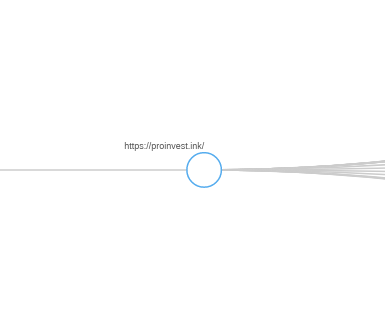

Next Spiderfoot identifies a part of the site called “Support” (there’s a few other URLs too, but I’m not going to look at those just now):

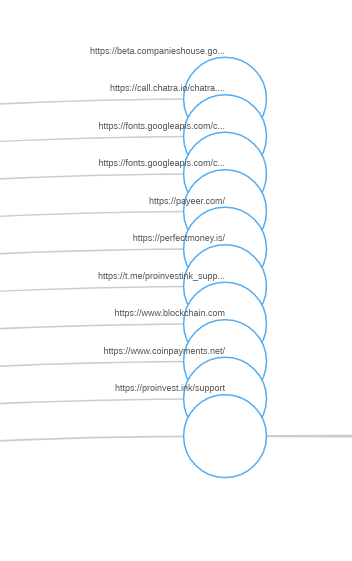

Following the graph across, we see that from the “Support” page, there’s a link to another page called “Representatives”, or as I like to call them “sock puppets run by scammers”:

Wouldn’t it be nice to be able to have found every single one of these sock puppets all in one go? Well guess what…

Dozens of sock puppets from Telegram, Facebook, YouTube, LinkedIn, Twitter, Google Plus, VK and other platforms, all linking back to this fraudulent website with the intention of duping victims into believing this a real investment scheme with real “winners”. There are too many to fit in one screenshot, but there are well over 400 profiles identified.

From Facebook:

VK:

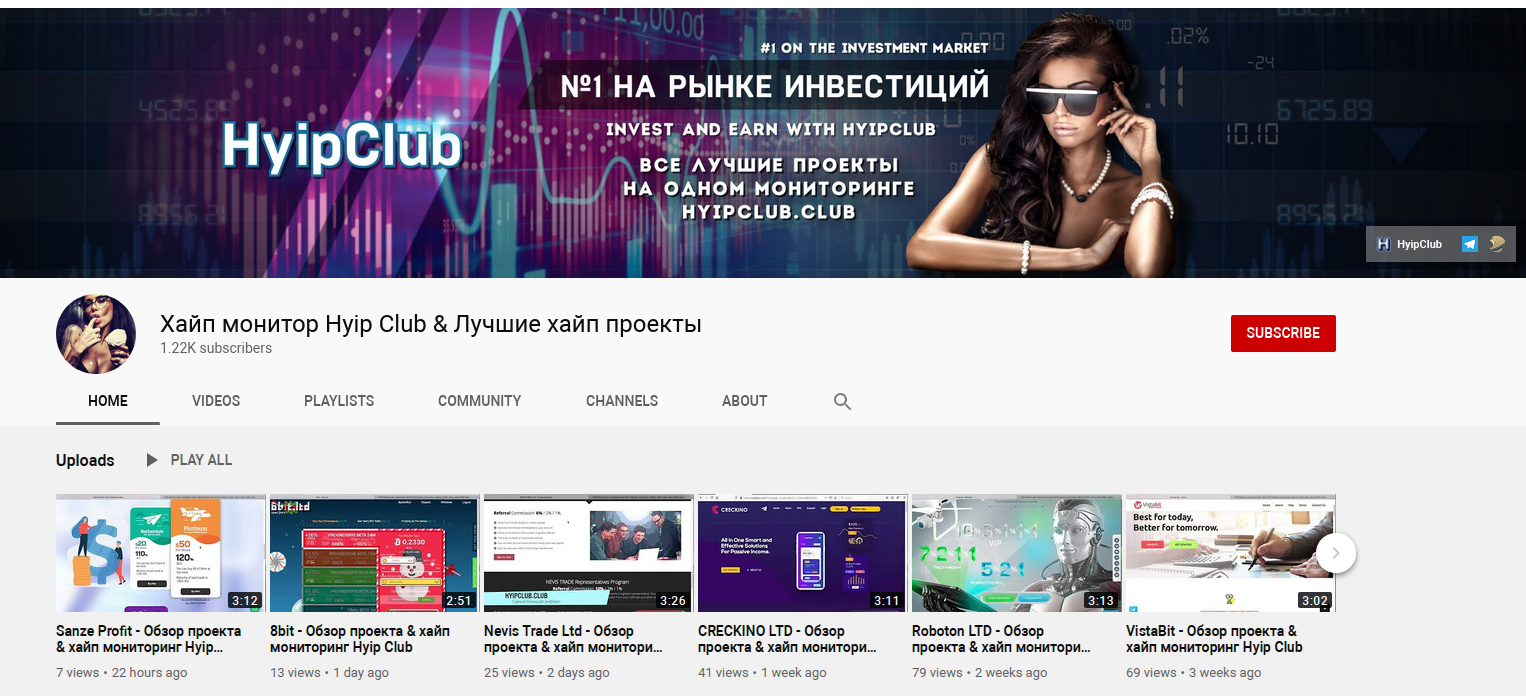

A YouTube channel helpfully previews several other associated crypto scams. The Russian link is not even disguised at this point:

And of course all the biggest London private equity firms use Telegram for customer support:

This just shows the real value of automated OSINT investigation. To do this manually would have taken hours or days. It only took Spiderfoot a few minutes to run this particular module.

Finding Tom_Proinvest

To work through these sock puppets and the never-ending chain of associated crypto scams would be another investigation in itself, so to finish off I’m going to focus on “Thomas Anderson”, the sock puppet who sent me the spam e-mail that triggered this investigation in the first place.

I’d already added the term “tom_proinvest” to the initial scan. The accounts module identified an associated Facebook account in addition to the Telegram account we already knew about. Unfortunately the Facebook account has been deleted, but there’s still a little we can do.

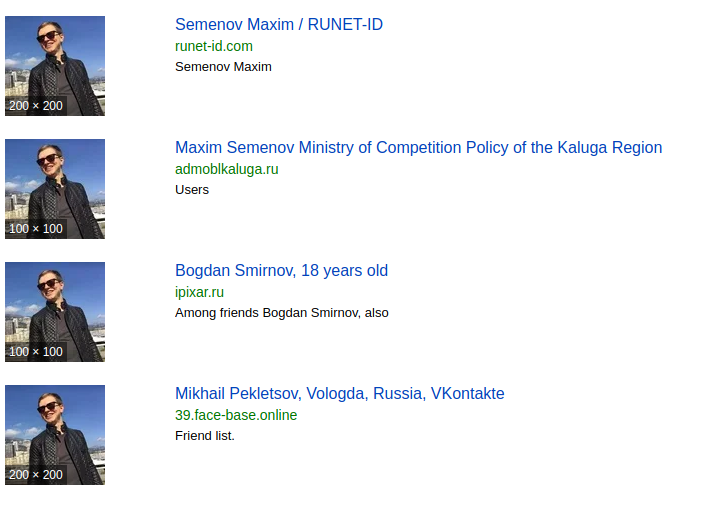

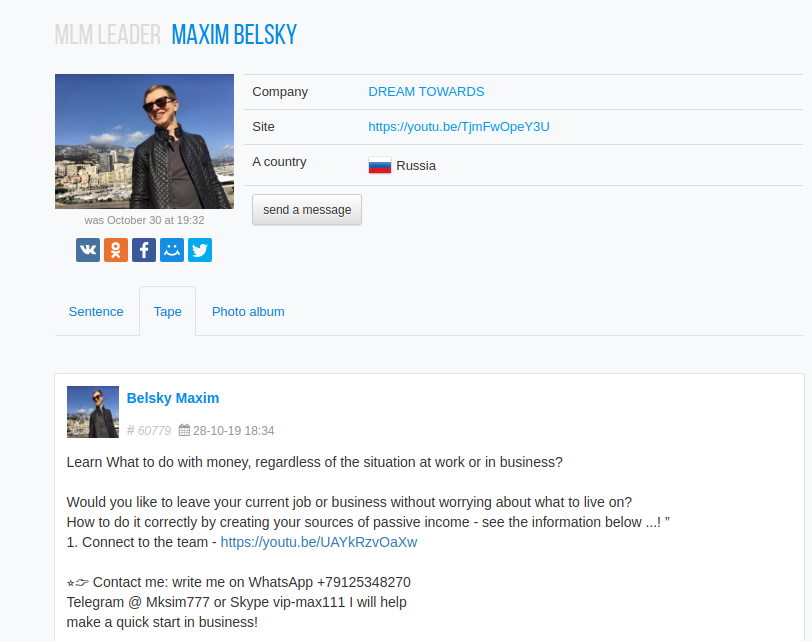

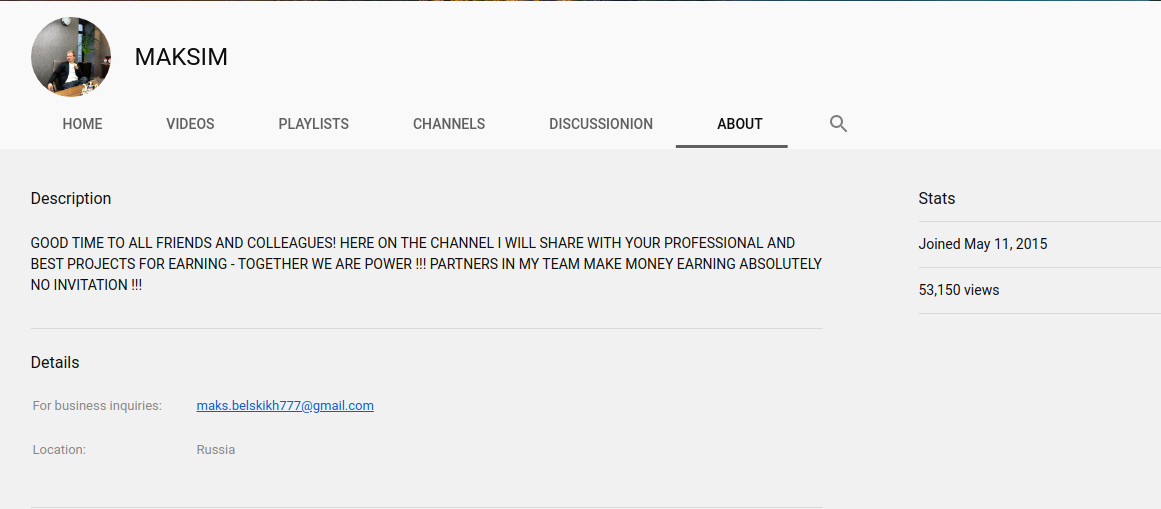

A reverse image search with Yandex immediately identifies the profile picture used to create “Tom”. Turns out he’s also known as Maxim Belsky, Maxim Semenov, Bogdan Smirnov, Mikhail Pekletszov, or even Dmitry Andreyevich:

And here is “Tom” being used to push yet another Russian crypto scam. There’s a mobile number, Skype account and another Telegram account that we could feed into Spiderfoot and continue our research.

In fact if we follow the link to the YouTube video that Tom aka “Maxim Belsky” is promoting, we find his YouTube channel, Gmail address, and lots of videos explaining how to run affiliate marketing investment scams. It is even possible that “Tom” really is Maxim, the crypto scammer who runs the YouTube channel.

There’s still quite a bit of the rabbit hole to go down yet however. It turns out that the picture of “Maxim” at his desk actually originates from the VK profile of a Ukraine-based “marketing expert” Oles Timofeev. There’s still a lot to explore – feel free to sign up for Spiderfoot and continue from where I’ve finished!

Conclusion

This little investigation started with a simple spam e-mail, but by using Spiderfoot HX to do the automated heavy lifting we’ve been able to widen the investigation very quickly and confirm that the website is not what it purports to be. It was suspicious from the outset of course, but Spiderfoot helps to bridge the gap between mere suspicion and being able to point to objective facts which help to prove the site is fraudulent.

Spiderfoot is a terrific effort multiplier. I could have investigated the scam manually but it would have taken days to gather the same amount of information that Spiderfoot did, let alone make sense of it and turn the information into some kind of coherent narrative. I don’t relish the thought of conducting these kind of investigations if they aren’t augmented with automated data-gathering of some kind.

While I was drafting this post I noticed that the Proinvest website has actually just been taken offline, but there will be plenty more to take its place!

If you’ve enjoyed this article, I’ve written some other articles on Spiderfoot here.

I did not receive any financial compensation for writing this or any other articles on Spiderfoot.