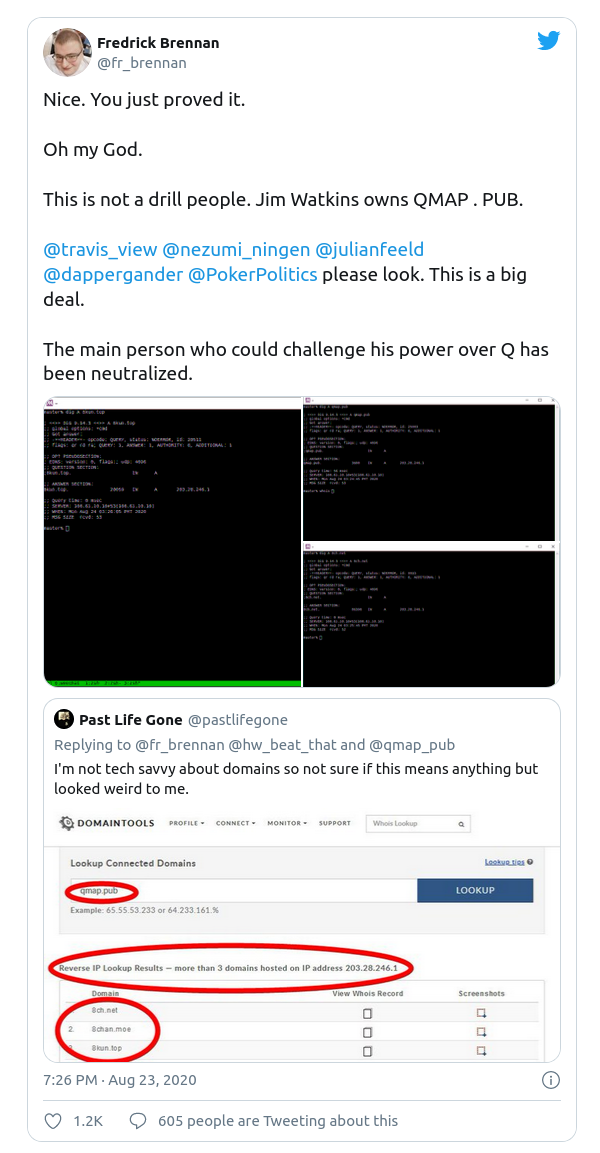

Twitter would not be Twitter without a daily dose of QAnon drama. Recently there were claims that since Q-drop archive site qmap.pub now shares the same IP as 8Kun proved that 8Kun owner Jim Watkins is Q.

I’m not sure that a reverse IP lookup by itself can really stretch that far, but it does raise some interesting questions. Firstly there’s a technical question – what is reverse DNS and why does it mean if two or more domains share the same IP? Secondly there’s a methodological question – what do you do with information that is ambiguous or unclear?

8Kun’s New IP Address

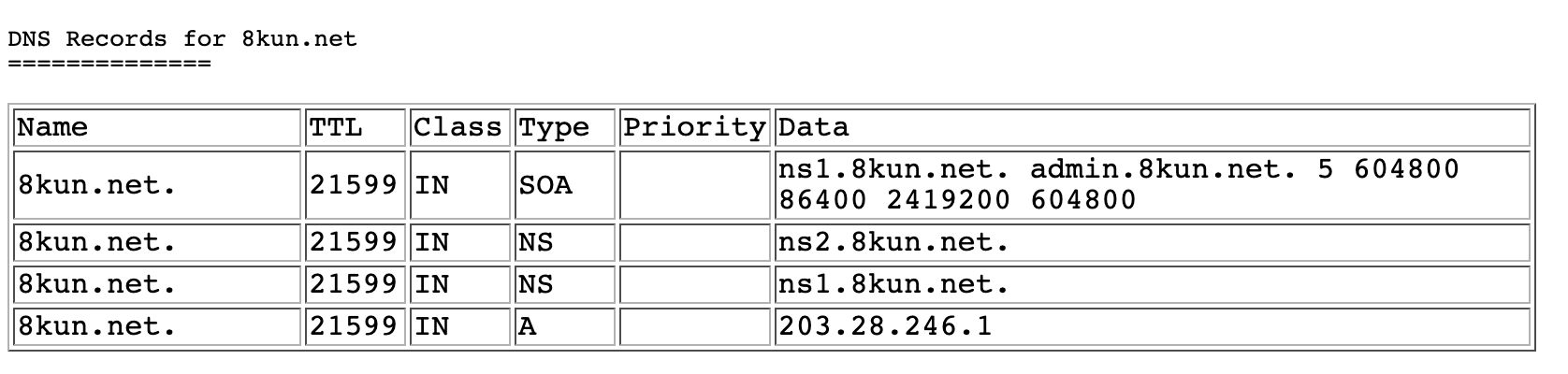

After losing the protection of Cloudflare last year, 8Chan/8Kun had to find a new home. There was a brief nomadic phase but eventually 8Kun settled for a new home on infrastructure provided by Vanwatech. A quick inspection of the DNS record confirms that requests for 8Kun are now directed to IP address 203.28.246.1:

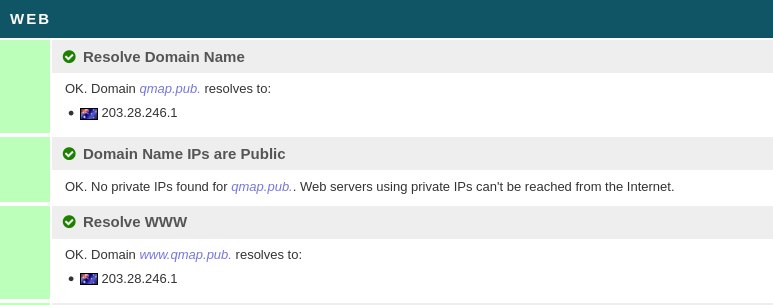

This IP address belongs to VanwaTech, a provider of Content Delivery Networks and other hosting services. Like Cloudflare, VanwaTech provides 8Kun with protection from DDOS and other security threats. Any DNS request made for 8Kun.net now points to this IP. Several other domains also share this IP, but since July this year Qmap.pub moved there too:

Finding out which domains share the same IP in this way is a useful OSINT technique but it is not without its limitations. But what is a reverse IP lookup and what can it tell us?

Reverse DNS Lookup

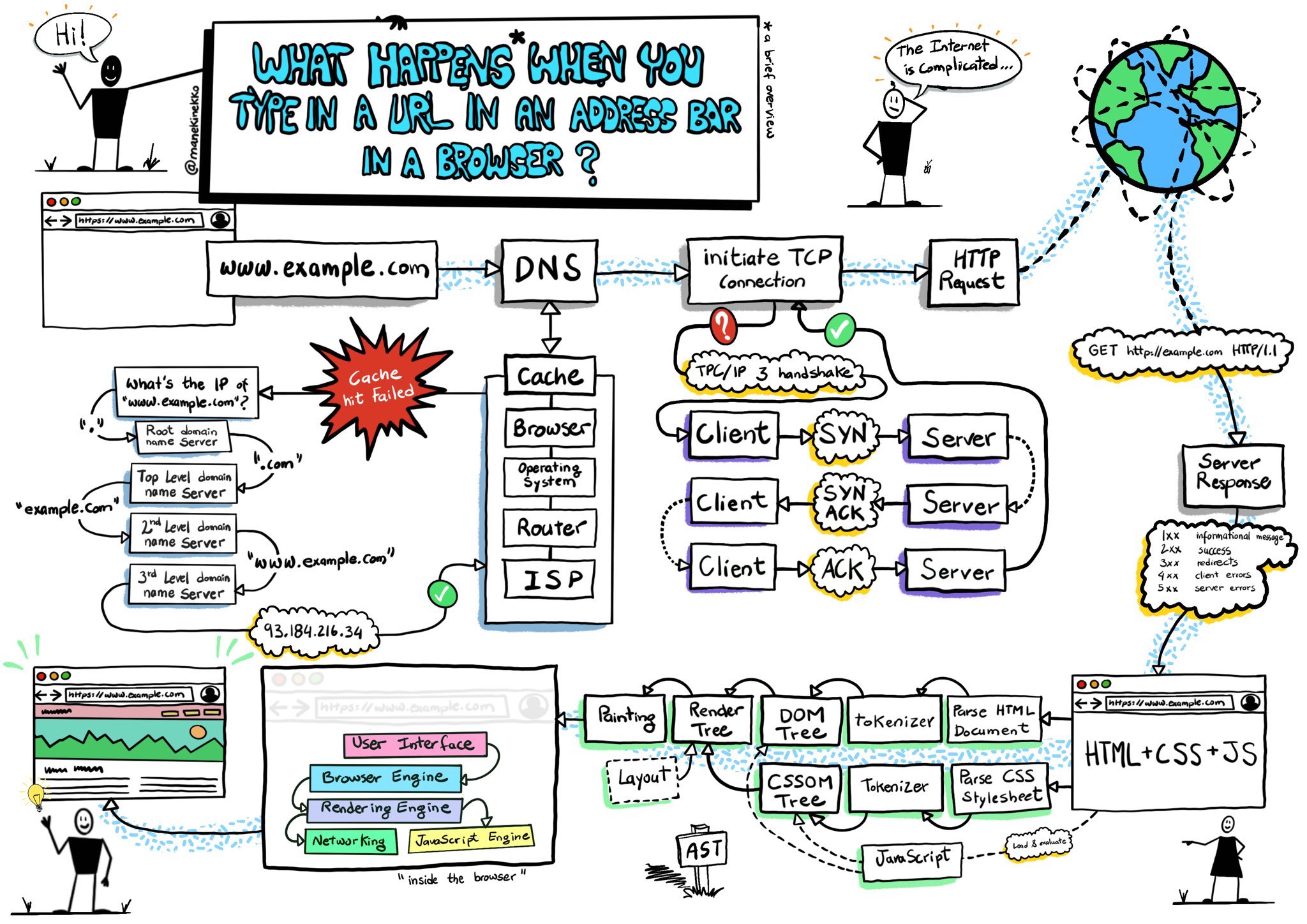

Every time you want to visit a website, your computer needs to know the current IP address where the website can be found. If you’ve visited the site fairly recently the IP address might already be cached in your computer’s memory, but if you haven’t then the computer needs to query a DNS server to find out. The DNS server tells your computer the correct IP address for the domain you want to access, and then your computer initiates a connection to the IP address in question. It’s a little more nuanced than that in reality, but that’s roughly how it works.

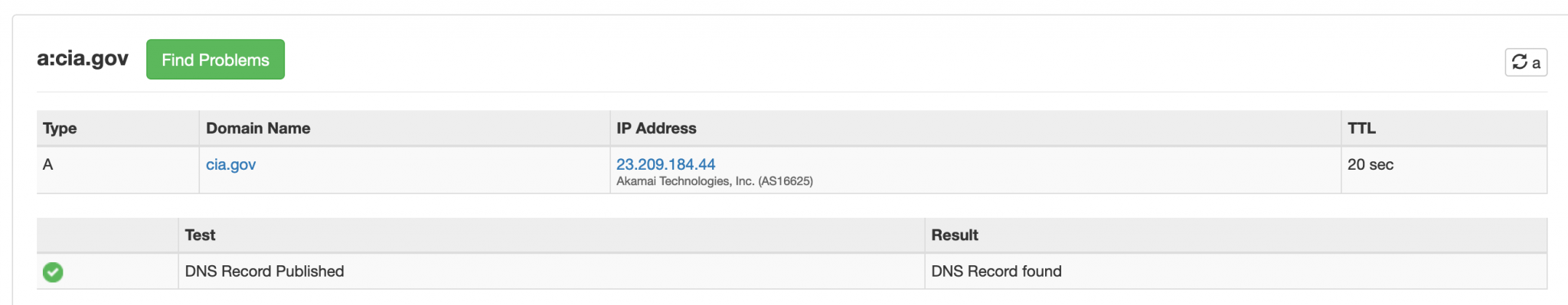

So how does the DNS server know which IP a domain is associated to? Ultimately there’s a chain of information that leads back to a DNS record published by the site owner. This record states which IP a domain can be found at. No matter how secretive and private you might be, if you want anyone to be able to access your domain then you have to publish a public DNS record. Even spooks need a DNS record. Here’s part of the CIA’s:

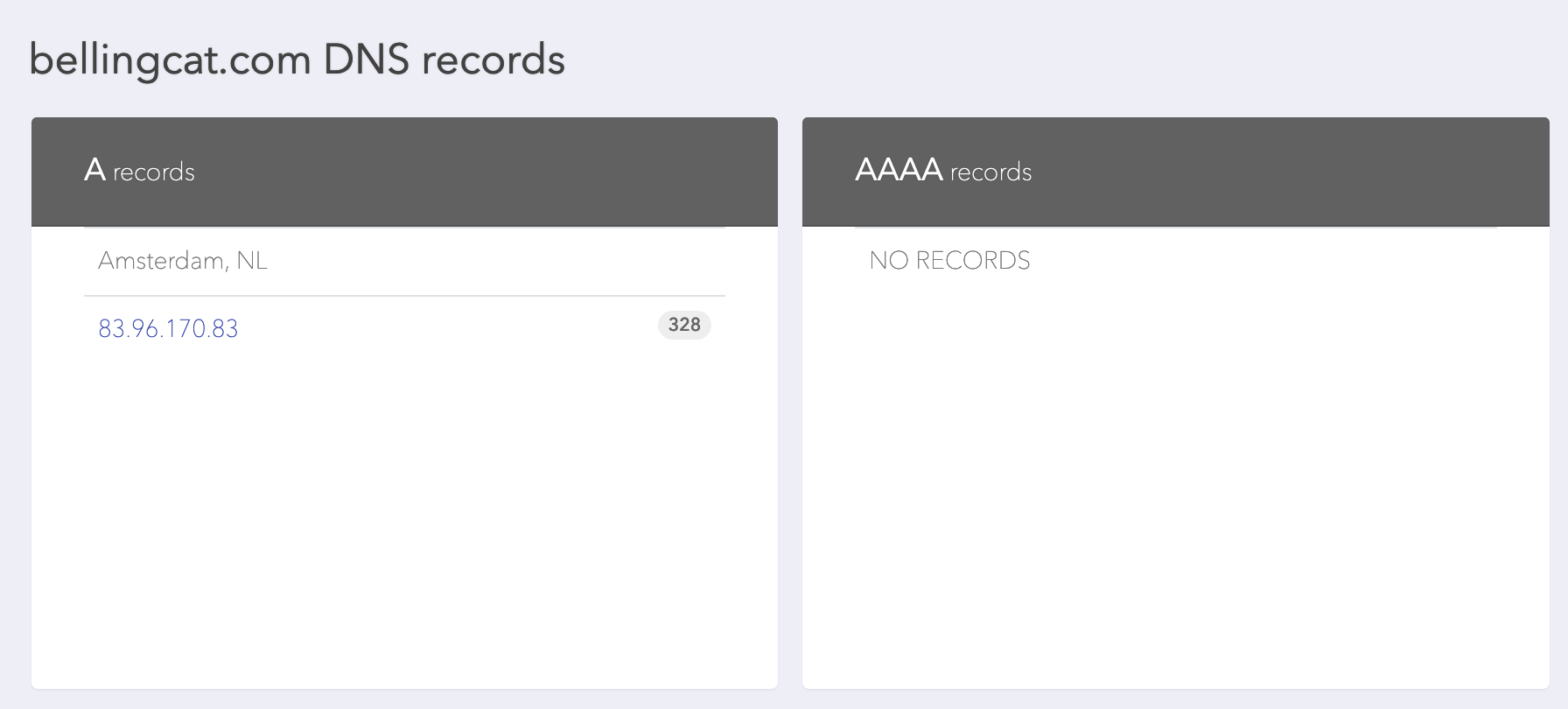

A reverse DNS lookup does the opposite of this. Instead of asking which IP is associated to a particular domain, it asks which domains share a particular IP. This information can be invaluable for OSINT because it often confirms an association between two or more domains that may not be apparent in any other way, although the association may extend no further than shared hosting arrangements. Here’s a DNS lookup for the domain Bellingcat.com (via Security Trails):

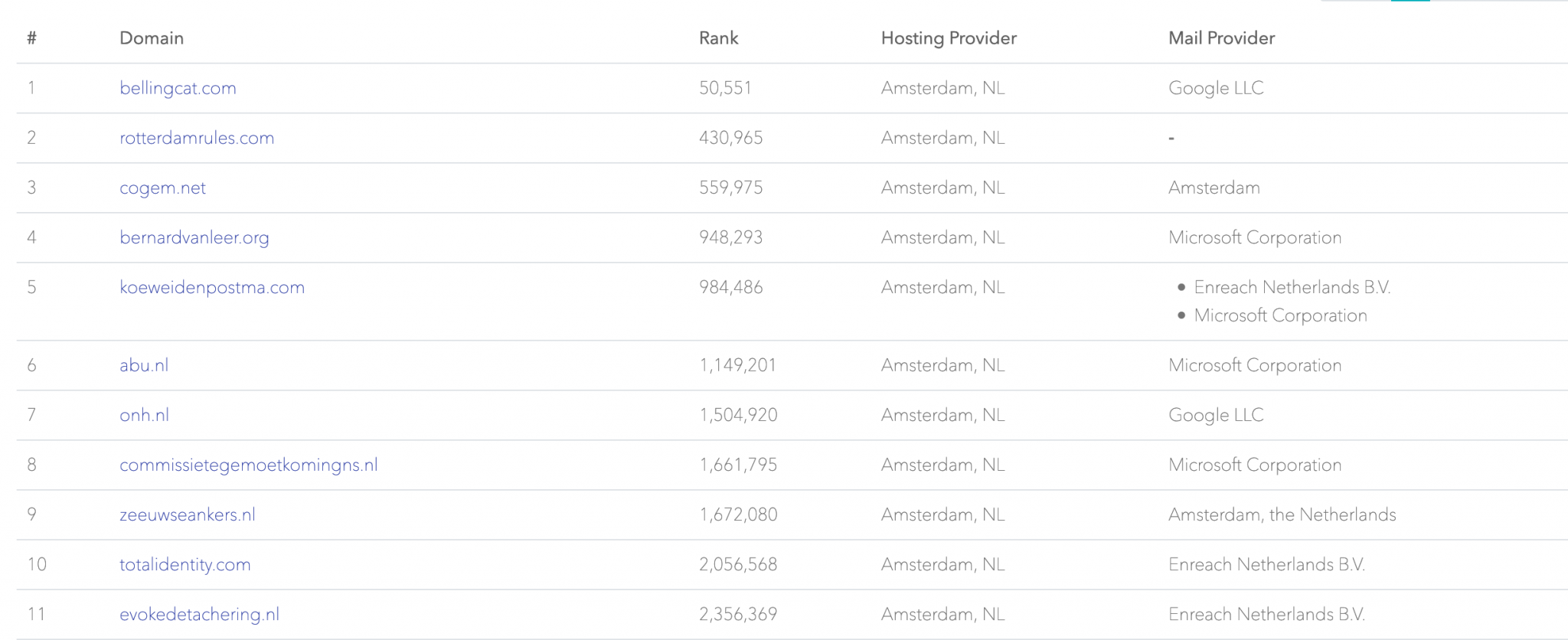

So Bellingcat.com is located at IP address 83.96.170.83 – along with 328 other domains. Let’s reverse the DNS query and see what the other domains are:

There are lots of other domains that use the same IP address as Bellingcat, Security Trails reckons that there are at least 328 different domains using the same IP, while DNSLytics has found at least 124. When it comes to reverse IP lookups different providers will often have conflicting information about how many domains share the same IP.,so it’s always better to check multiple sources.

So what does this mean for Bellingcat? How are they connected to the hundreds of other websites that share the same IP? The reality is that they have no connection other than the fact that they are all customers of the same hosting company. It’s an association of sorts, but it’s a very weak one. In almost all instances where multiple domains share the same IP a common hosting arrangement is just about the only connection that it is possible to be sure of. Any other claims we might wish to make about links between domains need additional corroborative evidence.

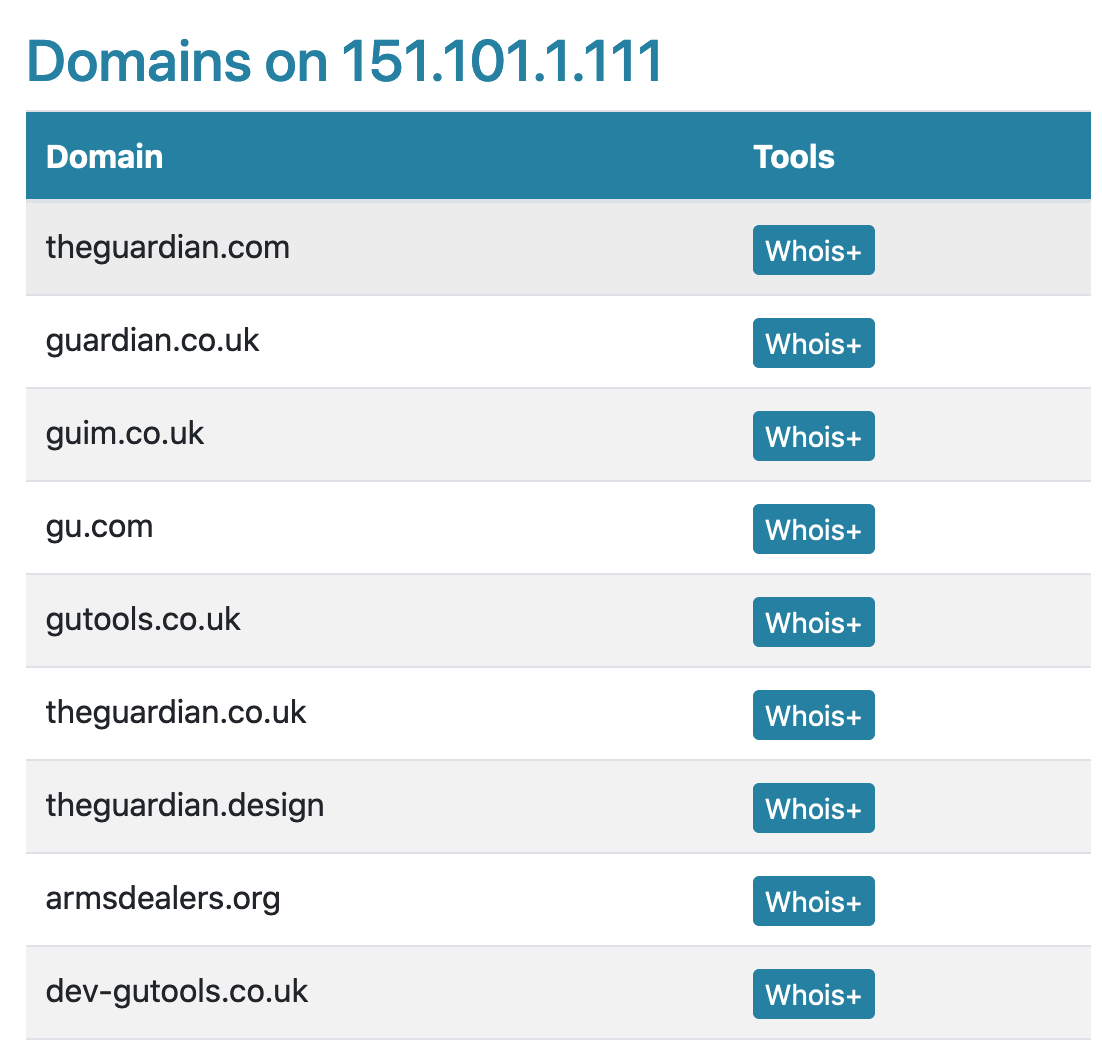

Just to add a little more confusion, sometimes the fact that multiple domains share the same IP is an indicator of common ownership. Let’s have a look at the hosting arrangements for The Guardian newspaper:

All the domains here are on the same IP and all (with the possible exception of armsdealers.org) are clearly associated to each other because they either redirect to the main Guardian website or else they are used by The Guardian’s dev/design teams.

So despite what we saw with Bellingcat’s site, sometimes a reverse IP lookup does reveal strongly associated websites after all.

If this makes reverse IP lookups appear to be inconsistent and ambiguous it’s because they are, at least when it comes to making claims about associations between websites. Sometimes domains might share an IP address but really all they have in common is the same hosting company or content delivery network. On the other hand sometimes the domains that share an IP really are owned or controlled by the same person.

What does this all mean for the original question about whether or not Jim Watkins is Q? It’s not a secret that Jim Watkins owns and manages 8Kun. So when the domain qmap.pub moved to the same IP address as 8Kun.net in earlier this year, this was taken by some observers as the final proof that Watkins was Q.

As we have seen the problem with this is that relying on reverse IP lookups alone is unreliable as an indicator of real-world associations. The only thing that a reverse IP lookup can say for absolute certain is that qdrops.app and 8kun.net both use the same content delivery network, Vanwatech. From a reverse IP lookup alone it is not possible to be certain of more than that. Jim Watkins might well be Q, but a shared IP address alone cannot categorically prove that.

Dealing With Ambiguity

This kind of uncertainty can cause issues in OSINT work. We like things to be black and white with nice clear answers, but the real world is rarely so kind. Website attribution is also a particularly difficult area to be absolutely certain about. So what do you do with this kind of information? The evidence does not conclusively support the conclusion of Twitter sleuths that Jim Watkins is Q, but we can’t just ignore the link either.

Most intelligence models have some kind of grading system to handle this kind of uncertainty. We don’t want to ignore what we’ve found, but we don’t want to overstate the significance of it either. So when it comes to reporting our findings we need to be truthful and accurate about what we’re saying and make sure we avoid sensationalism. We can try to avoid language like “certainly”, “conclusively”, “absolutely”, “never” or “always” and instead qualify our findings with language like “tends to support…”, “tends to undermine”, “partially corroborates x, but y remains unclear”, and so on. So instead of wrongly declaring “Jim Watkins is Q” based on a reverse IP lookup, we could say “8Kun and qmap.pub share a common content delivery network” or “there is a correlation between 8Kun and qalerts.app based on a shared IP address”. This is not as exciting, but is more truthful, and that is what matters.

If the first part of dealing with ambiguity in OSINT is to be accurate and honest about the limitations of what we find, the second part is to have an ongoing plan to try and eliminate as much of the ambiguity as possible. We don’t stop just after a reverse IP look up. What else do we know? What do we need to find out? What other sources of information are there? Would it be a good time to introduce another round of gap analysis to try and develop our hypothesis a little further? There are plenty of other tools in our kit bag and plenty of other lines of enquiry to follow.

If you’re interested in reading further about the infrastructure behind some prominent Q-affiliated sites and Vanwatech I highly recommend this long Twitter thread by @Redrum_of_Crows as a good place to start.

Pingback: Comme une aiguille dans une meule de QAnon – Flint Dimanche